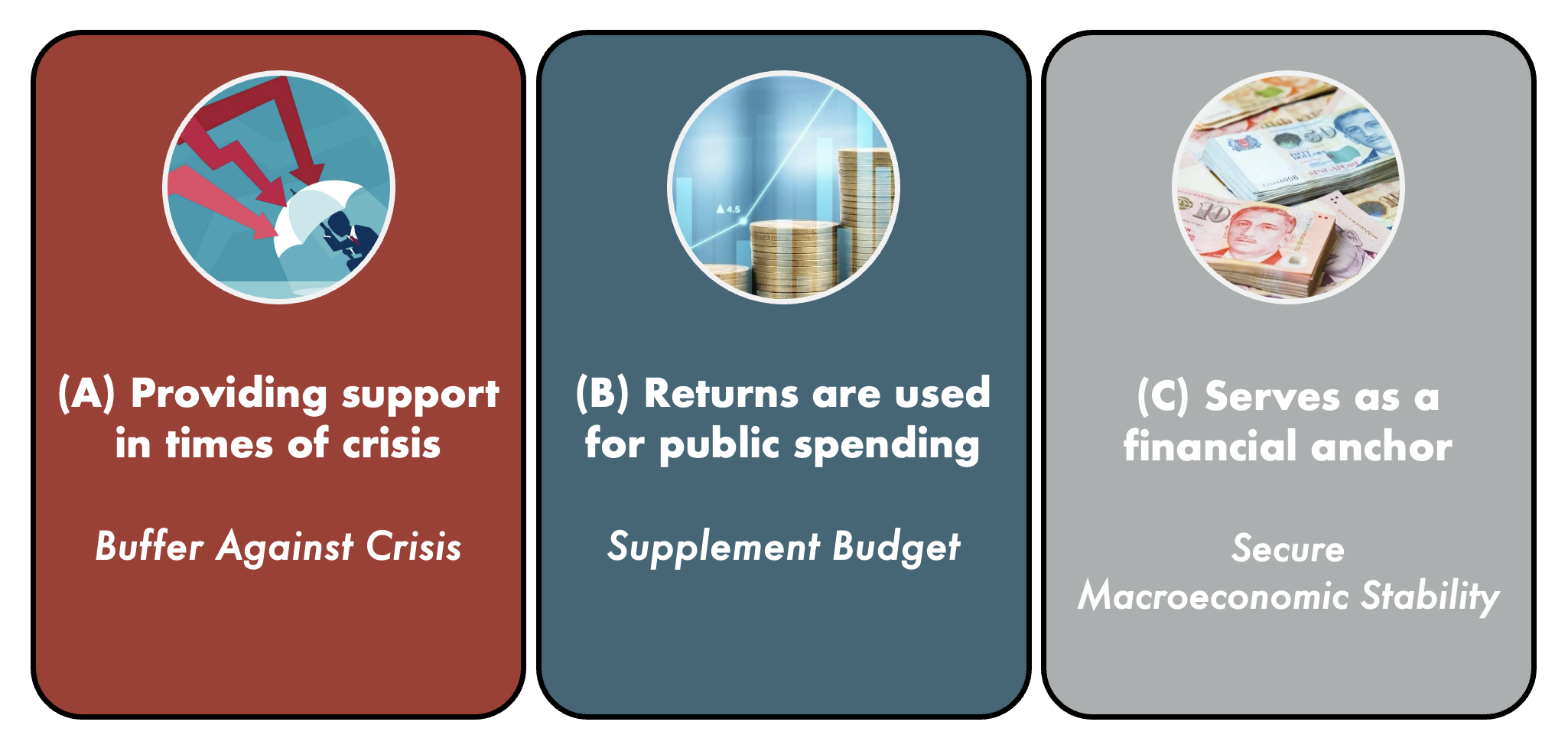

What Are The Reserves Used For?

Provides support in times of crisis

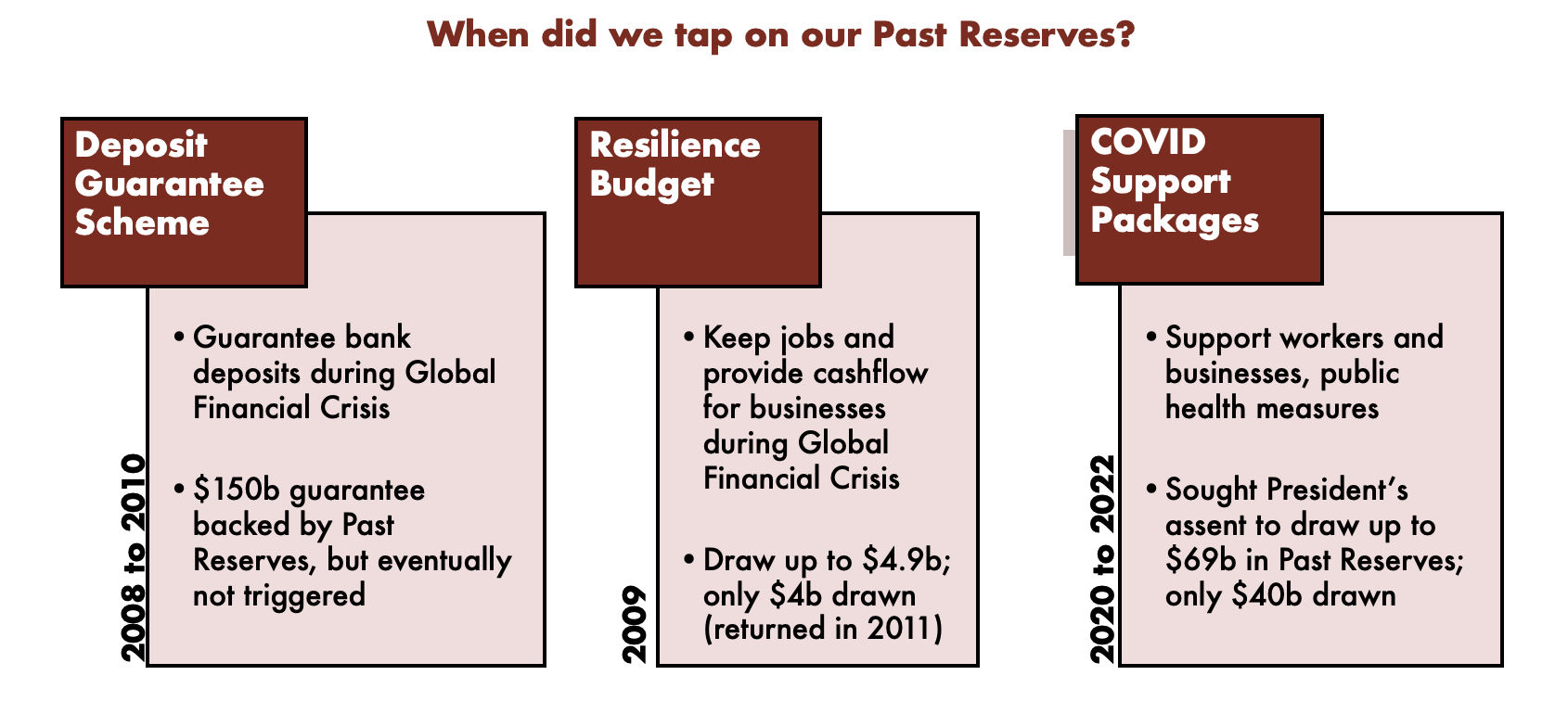

The reserves ensure that Singapore can respond decisively during crises without compromising essential services and incurring debt for future generations. For example:

- During the Global Financial Crisis, we drew on Past Reserves to subsidise employees’ wage bills and improve companies’ access to credit.

- In our fight against COVID-19, the Government drew about $40 billion from Past Reserves for COVID-19 response measures across FY2020 to FY2022. By tapping on the reserves, the Government was able to fund public health measures as well as economic and social support measures, to save lives and protect livelihoods.

The ability to tap our reserves in a sustainable manner is a significant financial advantage for Singapore. Our situation is quite unlike that in many countries that have to service their debts and other liabilities from their budgets on an annual basis, and consequently either raise taxes or engage in further borrowings so as to service current borrowings.

The few other countries where Governments are able to derive a revenue stream for public spending are typically those with substantial reserves of natural resources such as oil.

Watch this CNA documentary for a first-hand account of the decision-making process behind the two rare occasions that the Singapore government tapped on Past Reserves.

Will the Government return the $40 billion drawn from the Reserves drawn during COVID-19 pandemic?

While our economy has recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic and we have seen some revenue upsides in recent years, spending pressures continue to mount as we care for our ageing population, invest in early childhood education, and keep Singapore safe from rising security threats like terrorism. We will also have to invest in our economy to keep Singapore competitive, and in coastal protection and energy transition measures.

With a structural increase in our medium-term spending needs, it will be challenging to return what we have drawn from Past Reserves.

There is no Constitutional or legal requirement to return the amount drawn from Past Reserves. Even as spending goes up, we will continue to keep within our means, and maintain a balanced budget over the medium term.

Contributes to public spending

The reserves support Singapore’s current spending needs through its contribution to the annual Budget. About 20% of annual Government spending is funded by the investment returns on our reserves through the Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC). Since FY2020, the NIRC has provided an annual revenue stream of about 3.5% of GDP on average. For the financial year which ended on 31 March 2024, the NIRC was about $22.92 billion.

The investment returns from our reserves provide additional resources for Government spending to benefit Singaporeans. This includes Government investments in education, healthcare, transport infrastructure, R&D and other areas to improve our living

environment and to grow our economy.

Today, the NIRC is one of Singapore’s largest sources of Government revenue for annual spending. At the same time, there have been calls to increase the NIRC, above the present spending limit of 50% of the annual investment returns.

The NIRC framework is part of a larger sustainable fiscal system.

The framework balances between the needs of today and tomorrow. It underscores the Government’s commitment to continue growing our reserves, while allowing the Government to tap on part of the investment income for current spending.

If we spend more from NIRC today, we would effectively be reducing the reserves available for future use, which might result in higher taxes in the future or reduced expenditure for our future needs.

Serves as a financial anchor

As Singapore is a small and highly open economy, inflation and aggregate demand are more significantly influenced by the exchange rate rather than interest rates. Singapore’s monetary policy framework, conducted by MAS, is thus centred on managing the exchange rate of the Singapore Dollar against a basket of currencies within a policy band.

The reserves enable MAS to conduct monetary policy and secure macroeconomic stability, by defending the value of the Singapore Dollar from major fluctuations. This helps to protect the purchasing power of Singaporean households and businesses, maintain investor confidence in Singapore’s exchange rate-centred financial system, and secure macroeconomic stability.

Understand more: Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC)

The annual Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) amount is published in the Government's annual Budget. NIRC comprises:

- Up to 50% of the Net Investment Returns (NIR) on the net assets invested by GIC, MAS, and Temasek; and

- Up to 50% of the Net Investment Income (NII) derived from past reserves from the remaining assets.

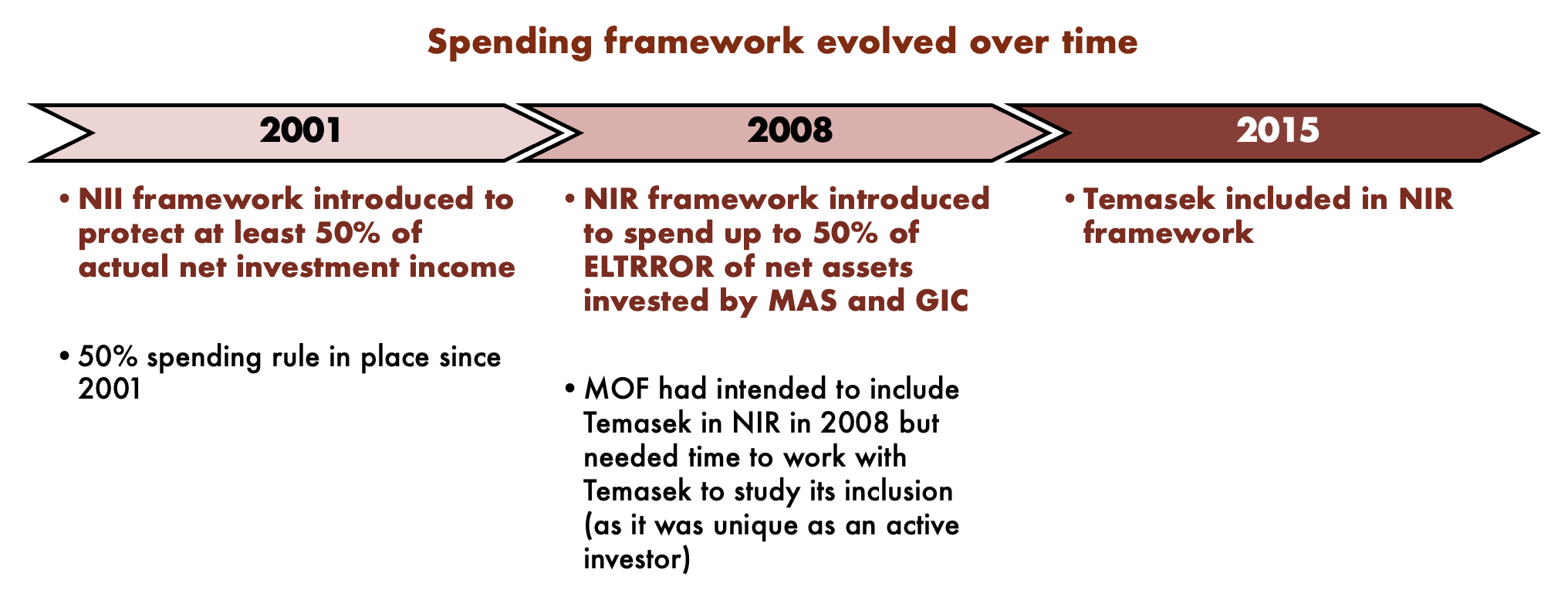

The NII Framework was introduced in 2001 to protect at least 50% of actual net investment income. NII refers to the actual dividends, interest and other income received from investing our reserves, as well as interest received from loans, after deducting expenses arising from raising, investing and managing the reserves.

The NIR framework was subsequently introduced in 2008, which allowed the Government to spend up to 50% of the expected long-term real return (including capital gains) on the relevant assets. The expected long-term real rate of return (ELTRROR) refers to the investment rate of return that can be expected to be earned over the long term, after netting off inflation. The expected rates of return are based on the judgement of experienced investment professionals in the investment entities.

- Spending up to 50% of the expected returns strikes a balance between current and future needs. It allows us to take in some investment returns for spending, while continuing to grow our reserves.

- Relevant assets are defined in the Constitution as the net assets invested by GIC, MAS, and Temasek, minus the liabilities of the Government (which include Singapore Government Securities and Special Singapore Government Securities). This ensures that we set aside returns to cover the costs of servicing our liabilities.

The NIR component was an enhancement in the following ways:

- Expanded the definition of investment returns to total returns, including capital gains (both realised and unrealised). This is more aligned with our asset allocation that is focused on maximising total returns over the long term. A spending rule based only on interest and dividends could have led to a bias toward investments that generate income rather than capital gains. This would be inconsistent with our objective of maintaining a diversified investment portfolio aimed at achieving long-term returns.

- Long-term expected rates of return (rather than year-on-year actual returns, comprising dividends and interest, under the NII component) rates of return are used used to smooth out the volatility of Government spending. For example, it ensures that the Government does not overspend in a bull market, and end up finding itself short of resources in a bear market.

- Real rates of return, i.e., net of inflation, (rather than nominal returns), are used to protect the purchasing power of our reserves. Otherwise, in a scenario of sustained high inflation globally, even if we were to earn reasonable nominal investment returns, our past reserves would be gradually eroded in real terms.

Together, the NIRC enhances revenues and ensures a fair balance between current and future needs.

Process to Determine the ELTRROR

There is a rigorous process in place for determining the ELTRROR of the investment entities.

- Before the start of each financial year, the rates are proposed by the Boards of the investment entities, based on detailed study and assessments by investment professionals in the three entities, who also draw on a range of external expert views.

- The Ministry of Finance undertakes a thorough review of the methodologies used by the investment entities to ensure that their approaches are sound and the estimated long-term rates of return for the financial year are reasonable. MOF will then seek President's concurrence on the proposed ELTRROR to be applied to the net assets invested by the investment entities.

- The President consults the Council of Presidential Advisers (CPA) before deciding on whether to agree with the Government's proposal.

- In the event that the Government and President fail to agree on any of the ELTRRORs despite discussions, the respective 20-year historical average real rates of return will be used to determine the NIR to be taken into the Budget for the financial year. The 20-year historical rate of return provides a neutral and pragmatic basis for resolving any dispute between the President and the Government, and avoids paralysing the Government of the day.

- After the close of the financial year, the Minister for Finance will certify to the President the amount of NIR that the Government has actually taken into the Budget, within the caps specified in the Constitution.

Are we "over-saving"?

Our reserves contribute directly to the annual Budget through the Net Investment Contributions Framework (NIRC). About 20% of annual Government spending is funded by the investment returns on our reserves. In addition, our reserves have played a crucial role in supporting Singaporeans through crises. For example, the Government drew on Past Reserves to support Singaporeans through the COVID-19 pandemic and the Global Financial Crisis.

The Government is not “over-saving”. While our reserves are growing, the size of our economy, the challenges facing our economy and complexity of our needs are growing even faster.

Returns on our investments are not guaranteed. They are subject to significant headwinds in the global investment environment – increasing geopolitical tensions, climate change, ageing populations, low productivity growth. We cannot choose at will when to slow down or increase the pace of returns.

Even at the current pace of accumulation, reserves growth will at best keep pace with economic growth.

We cannot predict what the future holds, what crises we will run into and how much more we will need. Keeping up our pace of saving will give us a safer buffer to meet future, growing needs.

Understand more about the Net Investment Return Contribution (NIRC) in the annual Budget.

SM Lee Hsien Loong in a CNA interview shares the inside story of the reserves.

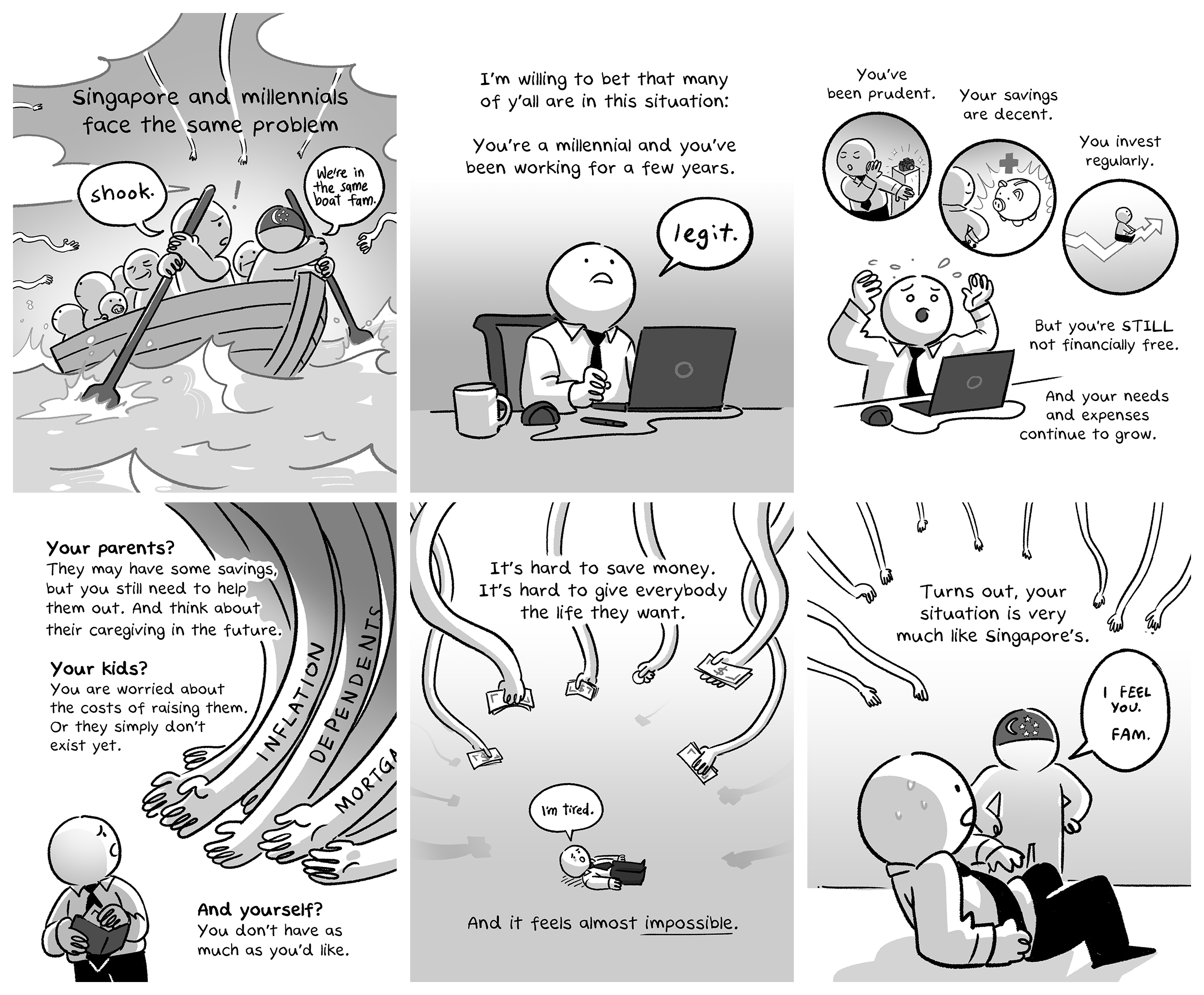

In some ways, how Singapore manages the reserves is similar to how we manage our personal finances. Find out how in "The Lessons About Wealth That We've Learnt From Singapore" and "Singapore and Millennials Face the Same Problem" by The Woke Salaryman.

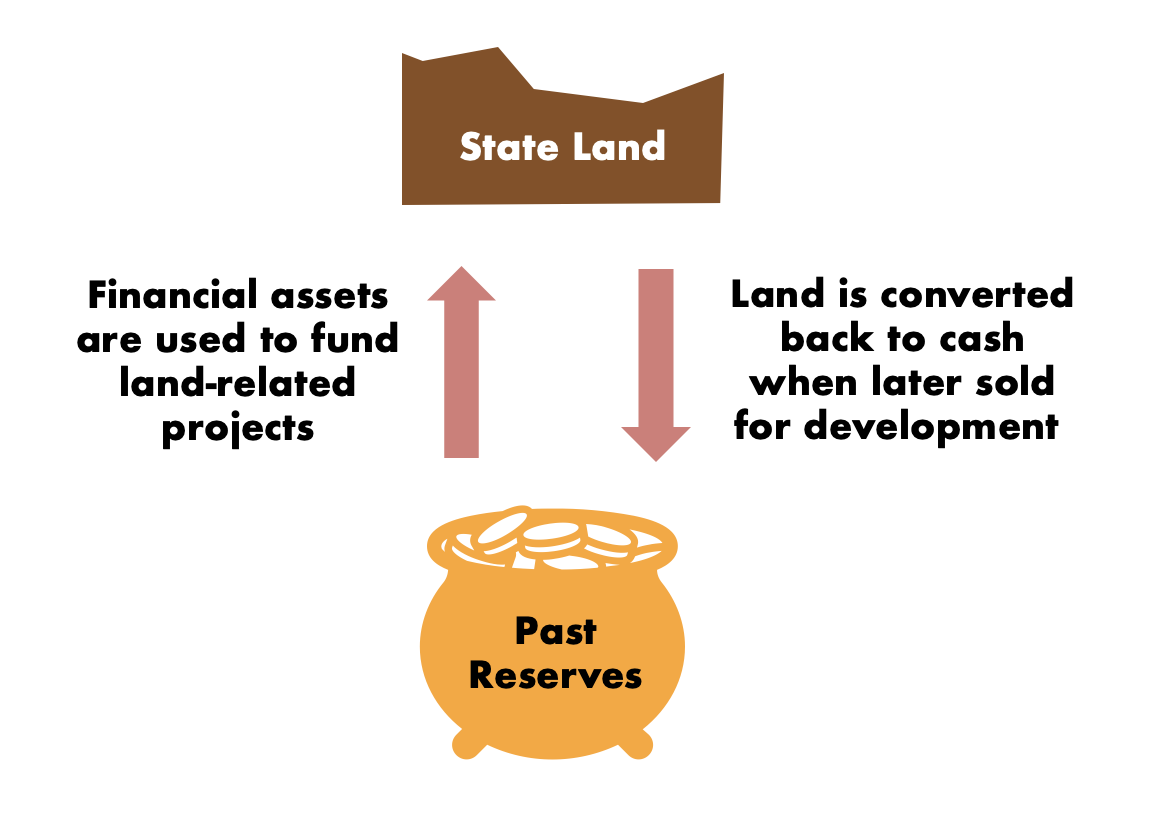

Holds our Land Bank

Land is scarce in Singapore, and it is our main natural resource. It is thus protected as part of the reserves.

Our Past Reserves are used to fund land-related projects such as land reclamation and the creation of underground space2 like the Jurong Rock Cavern as well as specific land acquisition projects like Selective En-bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS)3. This is a form of asset conversion, from a financial asset to a physical asset. The land created or acquired forms part of our State land holdings and is protected as Past Reserves. Further, when such land is subsequently sold, the proceeds accrue fully to Past Reserves to ensure that there is no draw on Past Reserves.

Spending from Land Sale Proceeds

When the Government sells land, it does not create new wealth – it merely converts the physical asset into a financial asset. When land is converted into a financial asset, the financial asset remains part of Past Reserves and cannot be used for expenditure.

- As the State holds ultimate title to the land, land which returns to the State at the end of a lease becomes State land once again and is protected as part of the Past Reserves.

- When that happens, there is no “profit” or net increase in the reserves. This is because the value of the “reversionary interest” in land (i.e. the right to resume ownership of the land at the end of a lease) is already protected as Past Reserves.

- In other words, when land is sold, the financial proceeds that the State receives make up for the State's loss of use of the land for the lease period, and not for the State giving the land away forever.

Spending the proceeds from selling land is simply akin to using up more of the reserves. Instead, the Government invests the land sales proceeds with the rest of the reserves, and spends up to 50% of the returns through the NIR framework.

This provides a more stable and sustainable stream of income over time than directly spending the land sales proceeds.

- First, land prices move in cycles and can be volatile. This would cause Government revenues to fluctuate with the market, creating too much uncertainty for the Government to plan for the long term.

- Second, if the Government relies on land sales to fund spending, it could develop a vested interest in keeping land prices high to maximise revenues.

When is State land considered disposed?

State land forms part of the Government’s Past Reserves. State land is disposed (or sold) when the Government issues freehold titles, or leasehold titles of 10 years or more. As the sale of State land is a conversion from a physical asset to a financial asset, the proceeds from the disposal of State Land accrue to Past Reserves.

State land is not considered disposed when the Government issues leasehold titles of shorter duration (i.e. for a total period of less than 10 years). In such cases, the proceeds can be spent.

Why is it important for State land to be sold at fair market value?

The fair market value of an asset is the price that it would fetch in a free and open market, between a willing buyer and willing seller. For State land, the fair market value can be determined by open tender, or by professional valuation. In the case of land used for public housing, the value is determined professionally and independently by the Chief Valuer, using established valuation principles.

When the Government uses State land (which forms part of the reserves) for development, including for public housing, the fair market value of the land must be paid into the reserves, to preserve the value of the reserves. Selling land at below fair

market value, or at no cost, would erode our reserves.

For more information on land valuation and public housing policies, please refer to MND’s resources.

- MND’s Aug 2023 Factually Clarification

- HDB’s resource on how BTO flats are priced

Financing Climate Action

The Government is currently studying long-term adaptation solutions to protect our coastline and land mass4 and how to best to fund them in a way that is fiscally sustainable and equitable across generations.

Guarantee CPF Interest Rates

CPF monies are invested by the CPF Board (CPFB) in Special Singapore Government Securities (SSGS) that are issued and guaranteed by the Singapore Government. This arrangement assures that CPFB will be able to pay its members all their monies when due, and the interest that it commits to pay on CPF accounts.

This is a solid guarantee. The Singapore Government is one of the few remaining triple-A credit-rated governments in the world. To elaborate:

- The Government is in a strong net asset position, i.e. its assets far exceed its liabilities (CPF liabilities in the form of SSGS are a part of these liabilities). The strong net asset position can be seen from the NIRC that is available for spending on the Government Budget. Over the past five years, the NIRC has provided an average revenue stream of about 3.5% of GDP per annum.

- What this means is that even after deducting all the Government's liabilities, the remaining net assets produce significant returns. The NIRC is drawn from returns on assets in excess of the liabilities, and is not the returns on gross assets. Further, as stipulated in the Constitution, the NIRC recorded in the Government Budget only comprises up to 50% of the expected returns on the reserves. The NIRC figures are submitted to the President's Office and audited by the Auditor-General's Office.

- If the Government's assets had not been adequate to meet its liabilities, there would have been no contribution from the investment returns on reserves in the Government Budget.

No CPF monies go towards government spending. Government borrowings from Singapore Government Securities (SGS) and SSGS cannot be used to fund expenditures. Under the Government Securities Act (enacted in 1992), the monies raised from SGS and SSGS cannot be spent.

These funds are comingled together with other sources of government funds (e.g., unencumbered assets5 such as government surpluses and land sales receipts) and deposited with MAS as government deposits.

In the process of conducting monetary policy, MAS may convert these funds into foreign assets through the foreign exchange market, accumulating foreign assets in the form of official foreign reserves (OFR), in order to moderate the appreciation of the Singapore dollar exchange rate. Excess OFR above what MAS requires to conduct monetary policy and ensure financial stability are ultimately transferred to GIC to be managed over a longer investment horizon, providing backing for longer-term Government liabilities like SSGS.

This CNA documentary explains how Singapore’s reserves guarantee CPF interest rates.

Understand more: Which investment entity invests CPF monies?

The Government’s assets are mainly managed by GIC. GIC is a fund manager, not the owner of the assets. It receives funds from Government for long-term management, without regard to the sources of Government funds, e.g. SGS, SSGS, government surpluses. The Government’s mandate to GIC is to manage the assets in a single pool, on an unencumbered basis5, with the aim of achieving good long-term returns. This allows GIC to take calculated investment risks aimed at achieving good long-term returns, without regard to the Government’s specific liabilities.

GIC’s long-term returns are thus not earned by managing only SSGS proceeds, but the combined pool of Government funds. If GIC were to manage SSGS proceeds directly through a separate, standalone fund, without the backing of the Government’s net assets, it would invest more conservatively, to avoid the risk of failing to meet obligations to CPF members – including not only a capital guarantee but the commitment to pay the minimum interest rates on CPF monies, regardless of market conditions. The fund would not be aimed at accepting risks that enable good long-term returns, but at avoiding any short-term shortfalls. The returns that such a fund would earn over the long term will be lower than what the GIC can expect to achieve with its current mandate of managing the Government’s pooled assets on an unencumbered basis.

Read more about how CPF interest rates are determined.

Are MAS and Temasek involved?

Prior to the formation of GIC, it was the MAS that managed these assets as the central bank. The investment of the assets was in keeping with the traditional approach of central banks, with large allocations to liquid, low-risk instruments. After GIC was formed in 1981, the assets were progressively transferred from MAS to GIC for management. This was to enable the assets to be invested in higher-risk instruments that could be expected to earn higher returns over the long term.

The SSGS proceeds have not been passed to Temasek for management. Temasek hence does not manage any CPF monies. Temasek manages its own assets, which have accrued mainly from proceeds from sale of its investments and reinvestments of dividends and other cash distributions it receives from its portfolio companies and other investments. Temasek also has its own borrowings and debt financing sources. The Government’s relationship with Temasek is that of its sole equity shareholder.

CPF interest rates are pegged to the returns on market instruments of comparable risk and duration.

However, there is also a minimum interest rate on CPF savings that protects members when market returns fall to low levels, such as over the past two decades. The computation approach for the CPF Ordinary, Special, MediSave and Retirement Accounts’ interest rates and the applicable minimum interest rates are listed below.

- Ordinary Account (OA): Computed based on the 3-month average of major local banks’ interest rates, subject to the legislated minimum interest rate of 2.5% per annum. More information can be found on CPF website.

- Special, MediSave and Retirement Accounts (SMRA): Computed based on the 12-month average yield of 10-year SGS plus 1%, subject to the current floor interest rate of 4% per annum.

The SMRA are for longer-term retirement and medical needs. To provide certainty for CPF members amidst an uncertain interest rate environment, the Government has extended the 4% floor rate for interest earned on all SMRA savings since it was first introduced in 2008.

The interest rate on the SMRA aims to be equivalent to what a 30-year SGS would earn, as 30 years is the typical duration for which SMRA monies are held. As the 30-year SGS did not exist when the Government made changes to the interest rate structure in 2007, SMRA rates were pegged to the yield of 10-year SGS plus 1%. - In addition, CPF members below age 55 earn an extra 1% interest on the first $60,000 of their combined CPF balances (capped at $20,000 for OA), while members aged 55 and above earn an extra 2% interest on the first $30,000 of their combined balances (capped at $20,000 for OA), and an extra 1% interest on the next $30,000.

There is no link between CPF interest rates and the returns earned by GIC. The CPF Board invests CPF savings entirely in risk-free SSGS issued by the Government.

The Government invests the SSGS proceeds together with its other assets through the GIC, which takes investment risks aimed at achieving good long-term returns. However, the consequence of taking risk as a long-term investor is that returns may be weak or even negative over shorter periods. Yet, the Government is able to guarantee CPF savings and pay the minimum interest rates on CPF savings regardless of GIC’s returns over any period, because the Government's balance sheet enables it to absorb risks. The Government has a significant buffer of net assets, i.e. assets which are well above its liabilities including its CPF commitments.

- For example, GIC experienced losses in investment value during the Global Financial Crisis, and low average returns for five years, before recovering (see GIC’s annual report).

- The Government was able to bear this investment risk because its substantial buffer of net assets ensures that it can meet its obligations.

This also means that GIC can invest without regard to the Government’s specific liabilities. This enables GIC to focus on achieving good long-term returns, in full knowledge that the portfolio will be exposed to significant risks over the shorter term as the markets experience cycles and volatility. The Government’s balance sheet would absorb these risks.

More Resources:

- DPM Tharman's reply to Parliamentary Questions on CPF interest rates and investment of CPF funds, 8 July 2014

- DPM Tharman's opening remarks at the "IPS Forum on CPF and Retirement Adequacy", 22 July 2014

- DPM Tharman's reply to a Parliamentary Question on how the Government's strong balance sheet enables it to weather market volatility and meet full obligations to CPF, 4 August 2014

Footnotes

[2] Past Reserves are used to fund only expenditure directly related to the creation of land, but not for the construction of infrastructure on the land.

[3] Past Reserves are used to fund only the land component of the total compensation of the acquisition costs.

[4] These include land reclamation projects, building of infrastructure such as polders and

seawalls, and the installation of equipment like pumps and localised flood barriers.

[5] Unencumbered assets refer to assets which are not matched to any liabilities. The Government has large, unencumbered assets, which are not matched to

liabilities. These assets were accumulated through past government surpluses, land sales receipts and the investment income earned on those assets over the years.